Apricots from the Damascus Room is an installation took place in the context of Apricots from Damascus exhibition in İstanbul. Within this context, İstanbul serves as a central hub and a backdrop to regional geopolitics. Although it never visually appears in, the city is physically and historically in the center of this story.

Apricots from The Damascus Room is based on the history, architectural layout and curatorial narrative of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It creates its own geopolitical narrative referencing art, mobility, exile, representation, restoration, orientalism, philanthropy and architecture. With a direct reference to title of the exhibition, the work’s narrative follows the routes of the refugees fleeing from Syria through Turkey, Greece, and finally to the ‘west,’ all within the confines of the museum.

The large photographs standing on the floor are consecutively from the Damascus Room, the Koç Family Galleries, the ancient Greek passage, and the exit of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This path can also be followed in the museum. The last photograph, in color, is the exit, and represents survival by reaching the ‘west’.

The Damascus Room, gallery 461, as described on the Metropolitan Museum’s website, is a residential winter reception chamber typical of the late Ottoman period in Damascus, Syria. The Damascus room was donated to the Met by Hagop Kevorkian, an Armenian-American archeologist, who was born in 1872 in Kayseri, formerly in the Ottoman Empire, and who died in 1962 in New York, the United States. Kevorkian was a connoisseur of art and an avid art collector, who graduated from the American Robert College in İstanbul, and settled in New York in the late 19th century. He was a seminal figure in the development of American knowledge and taste for Eastern artifacts. Kevorkian’s Armenian heritage connects to the title of the exhibition, as Armenians are known to have cultivated apricots since the 1st century AD. The Latin name for the apricot is Prunus Armeniaca, the armenian plum. Kevorkian cultivates a taste for the Damascus Room in New York, among the Metropolitan Museum’s viewers.

The Koç Family Galleries, galleries 459 and 460, display carpets, textiles and Arts of the Ottoman Court between the 14th to 20th centuries. The galleries provide a comprehensive overview of the multilayered nature of Ottoman patronage. The İstanbul based Vehbi Koç Foundation funded these galleries at Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rahmi Koç, who is the vice president of this foundation, and honorary trustee of the Metropolitan Museum, played a significant part in this donation. He was born in 1930 in Ankara as the only son of one of Turkey’s wealthiest man at the time, Vehbi Koç, He, too, attended the American Robert College in İstanbul after his primary education in Ankara.

Looking back at the photographs, we continue on from The Damascus Room and Koç Family Galleries, and into the final passage through gallery 153, part of the Greek and Roman Art section. Here, works from the 6th century include examples from the Museum’s distinguished collection of Panathenaic amphorae, or large ceramic vessels, amid other works related to ancient Greek athletics. In the center of the gallery are large-scale Roman-period marble copies of bronze statues originally created in Greece during the fourth and fifth centuries but, which were lost or melted down over time. The original marble statues from the fourth century B.C. are shown nearby the crowning sculptures of tall Athenian grave monuments.

The apricot, the refugee, the museum visitor, all of which survives travel through all of these places and times, now makes it to the exit. The last photograph shows a blue sky, a free flying bird, and an asymmetrical composition of the Fifth Avenue facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

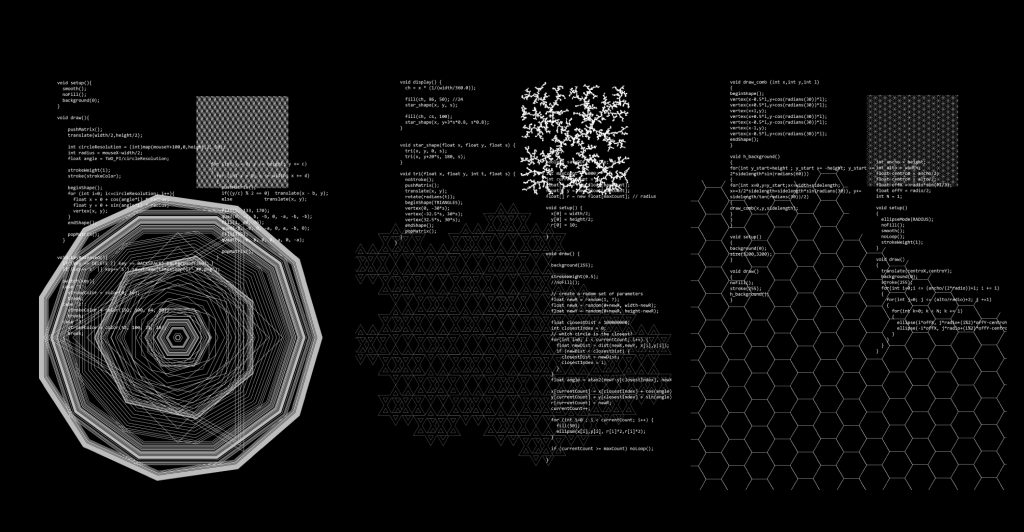

The wall of the installation Apricots from the Damascus Room begins with the map of the Metropolitan Museum, which is included in the museum guide and published in seven different languages, Arabic among them. These maps work as the key to the installation: the visitors can follow the route that the installation follows. The maps are followed by detail images that correspond to the large spacial photographs beneath them. The images are abstract islamic tile patterns, their missing parts and restoration details juxtaposed with the corresponding graphic code created imitate these patterns. Immediately following are the images of marble busts which are also the missing pieces of the sculpture that appear in the corresponding photographs below. These busts are gazing in multiple directions, and away from the path. Finally, a portion of the genetic code of prunus armeniaca is displayed on a mirror next to its biological illustration. This code represents a certain part of the gene sequence which relates to the survival of the apricot in different environments.

The work is located in a transitional space within the SALT Galata building. The larger photographs leaning against the wall make reference to the transitional concepts within the exhibition, and also refers to other works in the show. The directional read of the work leads the viewer’s gaze back out through the window to the city of İstanbul, once and again the center of mobility and transition.